A text by Albert Suissa for Lena Zaidel´s catalogue of the exhibition: Street Wolves, 2013, Jerusalem Artists´ House

Holiness – Hidden Face / Albert Suisa

In Lena Zaidel´s language of painting, whose use of line transforms the objects it depicts into a space unto itself, the first wolf appears in a seemingly infinite void unbound by definitions of space and time; “Untitled” serves also as the wolf´s metaphysical definition. The “darkness” in this painting had already undergone phenomenological preparation in the painting series Covers and Monastery, as Zaidel distilled from the works a neutral and independent background for the wolf´s arrival. The darkness in which the wolf prevails is not an absence of light but rather an effect that demonstrates the wolf´s absorption into and conjoining with the world. It is darkness that represents a being-consciousness that is no longer human. The world appears as though to itself; appears and reverberates in the animal´s unifying and undiscriminating eye. “The animal is in the world like water in water,” says George Battaile, and this painting, in and of itself, says just that – there is no barrier of “being” between wolf and water; rather, an absolute, conjoining equality exists between them and the world they permeate, to the point where everything is nothing but water in water. This all-conjoining equality is based on absolute, mutual indifference between wolf and water: the wolf is drinking the water, and the water may be drawn into that which draws it. But most importantly, if we set aside for a moment the act of painting itself, no subject whatsoever is present here, and therefore there is no form of “consciousness” that could formulate these statements. And yet, the viewer´s consciousness is bruised by the presence of the beast in a space she knows nothing about, or for our purposes, the viewer still does not know if she herself had been “expelled” from or whether it had been made permanently inaccessible to her. This is a disturbing and shocking gaze: after all, the beast is not only an object (it is drinking water!), yet its utter indifference revokes its subject status. What, then, is the meaning of the world of objects in which no human may be reflected from the animal´s eye?

This question emerges yet more acutely from the next painting. Still in that same tenebrous, measureless space, a perplexing encounter takes place between wolf and lemon. The lemon, the “object” shining with a blinding light, functions here as an eye that suddenly opens in the conjoined space and turns the perspectives one against another, without giving up on its own mystery. The luminous lemon in the world´s gloom mediates between the viewer´s gaze-consciousness and the meaningless gaze of the wolf-beast at something that is utterly meaningless to it (the wolf does not even eat the lemon). The viewer´s consciousness “bruised” by the lemon places it halfway between “thing” and concrete object; that is, midway on the road to the familiar and segregated human order of reality. Yet the feedback from the beast´s meaningless gaze at the lemon continues to bruise the viewer´s consciousness, disturbing it, fracturing the order of reality.

These two wolf paintings (both without a title) are the works that open the first series in the current exhibition, with the seemingly puzzling title All the Places are Holy. Zaidel´s paintings of wolves in Jerusalem have inherent political and social agendas, but I chose here not to discuss that aspect of them, because unlike the song of Israeli musician Corrine Allal, a line from which gave the exhibition its title, Zaidel´s paintings are clear of any irony or direct political statement. On the contrary, they possess a mesmerizing naiveté, which may be described either as Symbolist-spiritual, mystical or philosophical. And yet, “all places are holy” is in fact a self-contradictory claim that risks meaninglessness: if all places are holy, then one could just as easily argue that no place can be holy. At most, this could be an ambiguous claim of the mystic, not of the clergyman, since, I know of no theology without a hierarchy between the sacred and the profane. And if all places are indeed holy, what does it mean?

The image or object that permeates space and becomes conjoined with it in Zaidel´s early paintings holds a profound dialogue with the “vacuum” that powerfully radiates from her later works, which are before us here. The “emptying of space” in many Symbolist works is a well-known technique meant to focus the viewer´s gaze and emotion. For some of the great Surrealists, the Symbolists´ successors, led by De Chirico, “emptying of space” became the thing in itself, the painting´s overall effect, including the psychological ones. In Lena Zaidel´s work, “emptying of space” is not meant to create another, surreal or mental, dimension of reality, but the opposite – to render it completely bare. The following is an attempt on my part to distil something singular and unique, something slightly vague yet very fundamental and profound, which forms the painting´s essential, consistent and independent core.

The intuitive question to be asked here is “What is the meaning of this relentless striving for premordiality, rite, shamanism, cave paintings; for an era when man and animal were inseparably bound together?” More specifically, what is the thing that was not only irretrievably lost to us, which we have been inexorably looking for, with yet greater urgency since the appearance of Symbolism; what is that thing that became detached from the hand of the cave painter and was swept away in the darkness of his primordial cave, at the very moment when he painted to himself the image of the animal that suddenly transformed from ally into game? What was that thing that we would have clung to in supplication, even for a moment or two, if we would have offered human sacrifices, animal sacrifices, if we would have burned offerings of oil, flour and incense, if we would have pranced senseless until our feet bled around calves or snakes, or if we would have painted once more wolves upon wolves in the plazas and squares of a holy city?

Well, if we could imagine the oscillation of gaze and consciousness between the images projected from the above paintings and what lies outside of them; that is, the act of painting and it being observed, the most basic or abstract notion that we could distill is that a “something” inheres, beyond the space that exists between revealment and concealment, rock and air, water and wolf, something that “is,” something “teeming.” This is the Being of “I shall be what I shall be” that lies beyond the reach of the human mind, beyond subject-object relations. In Symbolist painting this mental phenomenon is called transcendence, but here, in Zaidel´s painting I will take a giant leap that calls for copious justification, and then I will take yet one more step forward and will call it, ever so humbly and carefully, holiness. Not a definition of holiness, and certainly not “representations” of it; only traces of its hidden face.

“The true life is absent. We are not in the world”

Arthur Rimbaud

Holiness, then, and the wolf – as a conductor, as a signifier of its absence of signification – is its hidden face. According to Lena Zaidel, this is the major difference between the perception of secular transcendence or the perception of holiness in anthroposophy, and the concept of religious holiness: there are no traces of holiness; there are only signifiers of its absurd and forlorn “possibility” beyond any existence. Therefore, by following the sequence of the wolf´s appearances in Zaidel´s paintings, as if they are a phenomenological pictorial storyboard, we are witnessing a process in which the wolf undergoes Symbolist distilment and becomes a signifier of the absence of holiness.

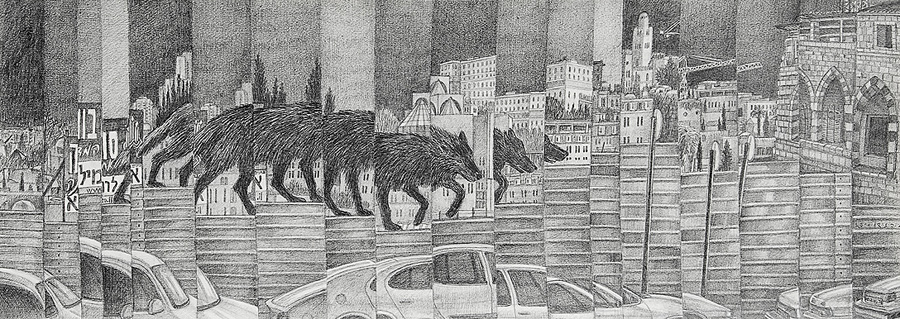

In the “Spring” painting, immediately after establishing the wolf´s function with a visual-philosophical claim, the beast is revealed in all its aloof cruelty as it appears at the edge of the civilized world, in its zones of material and mental excess of commodity and waste, while in the background, behind the “fence,” peeks its submissive nature, the city block, the place of “dwelling,” the gloriously renewed platonic cave of yore, as a congested, cloistered sheltering world. With her characteristic ironic, direct abundance, Zaidel already plants here the shielding symbols of the human mind, the very symbols that are repeatedly emptied and refilled, logos of Mey Eden mineral water and Spring soft drink brands, the tastes of life become waste at the feet of the beast, along the fence, on the other side of which waste and holiness are one and the same thing – absence. The fence, in whose shade the beast walks along as a symbolic ally, is perhaps the most conspicuous signifier in this series, simultaneously overt and covert, after the wolf-beast. The predominant meaning of the fence that is being erected in the paintings with the wolf´s mediation is just that: the polar opposite of the meaning of the walls of the Platonic cave, barriers that shut human consciousness away from the supreme and the sublime. The walls and fences surround holiness as if it was dangerous, as though it should be drained out of life in the cave and cordoned off outside of it.

From here onward, like a plague, the wolves indiscriminately raid city sites, the Temple Mount or commercial and industrial centers, nameless crossroads, monasteries or public buildings, back yards or city center squares. This creates the impression of an apocalyptic vision that the wolves disseminate, which is later intensified by the appearance of fish as the inhabitants of an aquarium formed by a sunken megapolis. But if we observe the work with yet greater care and overcome the Symbolist melancholy and the comforting “fascination” with the prospect of death by the kiss of Atlantis, we will see that the signifier´s impact, which strives nonetheless to induce the phenomenon to become a pictorial visual representation, is the heart of this painting. In the series All the Places are Holy, the wolves, as said, are conductors of holiness in a desolate urban landscape in which the absence of humans, despite having the odd signification, cries to the high heavens. And yet, let us not forget: all of the paintings are laden with living human metonymies: the opaque vehicles seem to drive of their own accord, flags wave in the wind, carts and sofas beg to be used, the groundworks are under way, and every now and again a human figure flashes like a hidden presence. This is not an apocalyptic vision, since humans are indeed present and existent; rather, like in Rimbaud´s verse, their lives seem to be absent. The next series, Broken-Hearted City Center serves as final proof to the correctness of this interpretation. Since, in this series humans return to occupy the sites from which they were absent a moment ago, only that now their world is fractured, broken, holding in its countless creases new insights that come from beyond the barricades, fences and walls of holiness and capital.

The conflation of this surreal emptiness with the wolves´ presence allows comprehending the meaning of holiness according to Zaidel. The moment that humans are left out of the picture, and all the more so once they are brought back, the paintings become filled with an insufferable amount of objects, symbols, puzzles, slogans, puns and surprising combinations, all of which convey a severed, rhizomatic fullness, without beginning and end, bereft of a sequence; a segregated immanence, deep and claustrophobic absorption in the wall of things that humans had created in order to shelter themselves from the supreme and the sublime. This is a dead-end rhizome with countless entrances and exits; a rhizome with an inward-facing funnel. These paintings seem to invite you to play pointless, infinite crossword or Sudoku puzzles in the familiar Game of Life, the futile trivia game of your world, crammed and compressed by the infinite manifold. The master project of the Old World – meaning, spirituality, cultic attachment to the supreme and the sublime, to infinity and fast depleting holiness – has been abandoned and forsaken. Did Rimbaud have in mind this Pavlovian reaction of human acts and thoughts when he implied that hell is already here, as a paraphrase on the well-known aphorism of Jewish theology, whereby “This world is a corridor leading to the World to Come?”

The wolves made their first appearance like a deep inner urge, like an invitation sent to primordial life forces to make themselves present at a time when persons that are close and very dear to Zaidel fell ill. The wolves proliferated when she mourned the death of her father, and two years later that of her mother and other loved ones. Death, which reaches every living thing, appears to be nothing more than the dwindling of life; hence, the death of father and mother appear as yet another barrier or protective wall of the power of life that crumbled in the face of lurking death. As in Jungian therapy, the wolves were meant to expel bitter death, to reinvigorate life. This aspect of the wolves´ symbolic healing and vital powers stands out in this painting. And yet, if we recall the unique and paradoxical aspect of the revealment and concealment of holiness, we may certainly wonder whether mourning procedures, the hundreds of traditional laws and customs, as well as the private ones, were actually invented in order to shake away from life the horrifying holiness that had clung to them because of the deceased, the person who had lived her life moment after moment and then suddenly and inexplicably became the worst form of defilement.

“The true life is absent.” Arthur Rimbaud

“And yet we are in the world.” Emmanuel Levinas

The paintings in the Broken-Hearted City Center series are a sequel to All the Places are Holy. The friendly wolves roaming freely between fragments of reality appear to testify that they have always been here, but our eyes could not see them. Life goes on in spite of the fact that everyone admits that it is fractured and possibly will never be healed. Zaidel tries to address several dimensions of this life. In the linguistic dimension, Zaidel adopts the concept of Bratzlav Hassidism of the cycle of crisis-fall-rise, captured in the mantra “Na-Nach-Nachman,” employing it in order to deconstruct the walls of language, which humans use in order to generate a productive and dynamic reality that denies the existence of crisis and fall; walls upon which humans build the walls of their own self-consciousness, which yet again project unto reality a display of normalcy. In “Nayeded Mad´a,” Magen David Adom ambulance, like the vulnerable and fragile reality that folds in like theater props, language also breaks down, protective tools and symbols in tow; and beneath the word fragment remains, new meanings emerge from beneath the solid façade of linguistic structures. The question “mi” (“who” in Hebrew), sunders the imperious “Mister,” which allegedly provides bread across the land, “mi mister?” (“who is the mister,” in Hebrew), with the ironic conclusion “zol!” (“cheap” in Hebrew. Mister Zol is a chain of discount supermarkets). Hence, it becomes the great mystery of the implicit boundaries of consumption. The “ma” (“what” in Hebrew) of “Hamashbeer” (the name of a department store; in biblical Hebrew the title of the person in charge of grain supplies), becomes fragile, shaveer, by undercutting the boundary of commerce and consumption, which is blood, life, presented here with a replica styled after an ancient pseudo-biblical dictum: “Blood for humans, donations!.” The blood that is elsewhere drained and thus leads to death, is resituated here as drained in order to become a life-saving donation.

But what is life? What is its meaning? And what for? These gnawing questions recur in many of Zaidel´s paintings. In a painting ironically entitled “The Art of Air Conditioning,” permeated by actual, controlled madness, the hodgepodge urban landscape underscores further the assorted parts of the lost language, its holiness and its ability to represent reality. “Crown Jewel,” which resonates like a biblical epithet for the heavenly Jerusalem, is nothing more than a sign declaring the name of a hideous building meant to raise the earthly Jerusalem, where the pathetic “big” is simply an aggressive “give” (the Hebrew consonants make up both words), to the lofty function of a nuptial assembly line. The yin-yang symbol, which stands for the harmony of opposites in the universe, is used here as the logo of an air conditioning manufacturer and repair service selling the artificial “art of air conditioning” as the complete obliteration of opposites in nature. Human loss of orientation and direction is manifested by the ubiquity of direction signs and road signs in the human landscape, while the movie advertisement of the lost Basic Instinct, for which our yearning grow the more we draw away from it, is represented by the galloping wolves that appear to be roaming aimlessly. Humans are the only creatures in the universe that need an ever-growing amount of direction signs in order to navigate the chaotic reality that they themselves created, including signs carrying their own image marking the danger that lurks at every step in a reality of subterfuge and peril.

Holiness, then, as a border concept, as lost meaning, certainly lurks about here by means of the wolves. The thought of the absence of something irretrievably lost behind the screen of a manifold of things and symbols without measure or purpose in this painting causes feebleness of mind, exasperation, triggers thoughts about the inescapability of the fate of a quicksand life. The big question that recurs in these paintings – which already echoed in works from the first of the Symbolists to the last of the post-Symbolists, Dadaists, Surrealists and Futurists – places a mirror before Rimbaud-esque desperation, placed alongside the radically optimistic humanism of the school of Emmanuel Levinas. In these paintings, like Levinas, Zaidel is saying in a low, dry voice, “And yet, we are in the world.”

The three triptychs, or giant trilogies at the center of the exhibition, “Fence II, “Fountain of the Lions” and “Y-M,” appear to address this state of mind, and I am still unsure whether they offer a genuine answer. As their names suggest, All the Places are Holy or Broken-Hearted City Center, they seem to vacillate between desperation and promise. Their particularly large format, which usually expresses in Zaidel´s work plenty and clarity, is used here as a sign for a long repose, focused intention; a repose during which a sigh is let out while rest still remains a possibility. It harbors the anticipation that after the rupture and fragmentation of Na-Nach-Nachman, the name as a whole, Nachman, “he who brings comfort,” will appear. But I am still unsure whether these paintings offer genuine comfort; they are still charged with the big questions of the paintings standing next to them, and yet they possess a moment of spiritual clarity of mind, of recess and temporary convergence. These paintings raise several questions, perhaps answers as well, that Zaidel uses as a concluding remark to the great Symbolist tradition and its successors. Below, however, I will concisely address the three main questions by the order of the paintings:

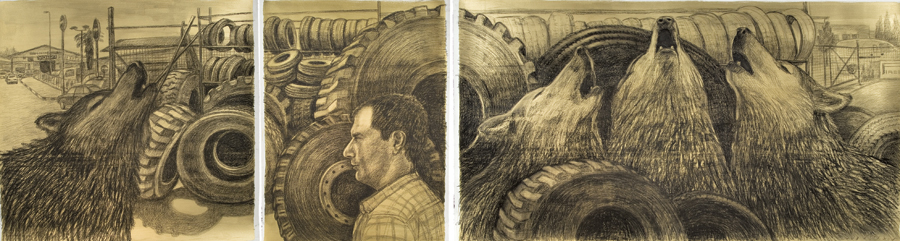

1.In “Garage 2,” the core of Symbolism´s main claim and origins stretches across the entire work: the Enlightenment, and most importantly the industrial revolution that followed it, not only undercut and overthrew the beliefs, values and symbols of the Old World; they threatened to make it disappear altogether and fill the world to the brim with the values of production and commerce, whereby even humans themselves became a legitimate commodity. The absence of any human presence from this space is chilling, and the effect of the opaque cars that appear to be driving of their own accord in the other paintings reaches daemonic proportions here, suggesting that “another planet” may be gradually overtaking human existence in “peaceful” ways. Both the howling of the beast and the blowing of the shofar, beyond their biological or ritualistic function, are acoustically excessive and startling, casting a terrifying mixture of guilt, terror and longing. In this painting, apart from the howling wolves that function as a signifier that has been lost, the absence of holiness – and even the absence of any trace of transcendence – is total and horrifying. The howling of the wolves, the howling of the Atiqa Qadisha, the mythical primordial holiness of God, is embedded here, instead of being heard is silenced by the howling of the modernist daemon basking in the orgy of production. The human figure placed in the center of the work appears to be making a titanic effort to discern the howl of the daemon from the howl of the beast-holiness. The fact that the figure torn between the howls is male and not female is not at all coincidental, as it is confronted with the two female figures in the work´s two other parts, discussed below, thus opening another well-trodden path of interpretation into Zaidel´s work.

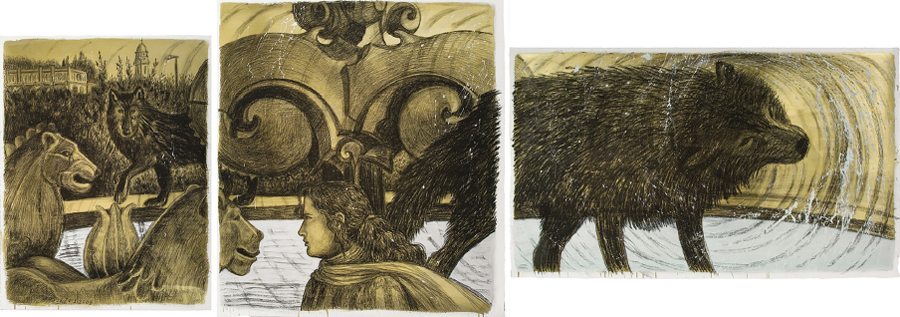

2.The woman, and the beauty ideal she stands for, is the most important paradigmatic figure in the Symbolist painting resurrected here in “Fountain of the Lions.” There is no other motif in Symbolist painting that suffered as much criticism suffused with irony, cynicism, ridicule and ultimately concealment and utter disregard by Modernism, which had thus run Symbolism into the ground, despite having internalized and appropriated its principles. In a certain sense, Modernism, or at least its pretension, does not seek to come to terms with its past through resistance, but rather craves its complete annihilation and banishment in order to face the vacuum left in the aftermath. In this sense, abstract and conceptual art became possible mostly after Woman had been banished from painting. “A car travelling at 100 mph is more beautiful than Venus of Milo,” declared the Futurist Marinetti, thus marking the transition from the sedentary beauty ideal of the Old World to the every-changing beauty ideal of movement and speed that quickly connected with the industrial powers of production and destruction.

In many senses, “Fountain of the Lions” is a very bold statement of Zaidel´s, particularly with the Catholic church in the background, here in Jerusalem, the cradle and bastion of this ideal since the beginning of time. The painting exudes harmony all around, but also frivolity, which emanates entirely from the presence of the wolves. One of them, with its rotating shaking movement, appears to continue the fountain´s serene murmur. The decorative element at the top of the fountain seems to protrude from the crown of creation, the woman at the middle of the work, who by that represents the ideal of the good and the beautiful from which the world may be built or destroyed. Is Zaidel insinuating that the woman and the beast maintain a bond, which opens up the possibility of holiness?

3.”And yet, we are in the world,” is not necessarily a denial of the claim that “The true life is absent.” We emphasize “And yet,” as a refusal to sink into desperation on the one hand, and as a demanding and grim point of departure that refuses to accept realist and palpable scarcity on the other hand. The symbol in the painting is manic-depressive, either resplendent or grieving, because it is always either yearns for or mourns over something that is absent from reality. Therefore, in Symbolist painting this insight usually appears as a sort of hallucination, false consciousness or near-madness, shrouded in a thin veil of melancholy and longing.

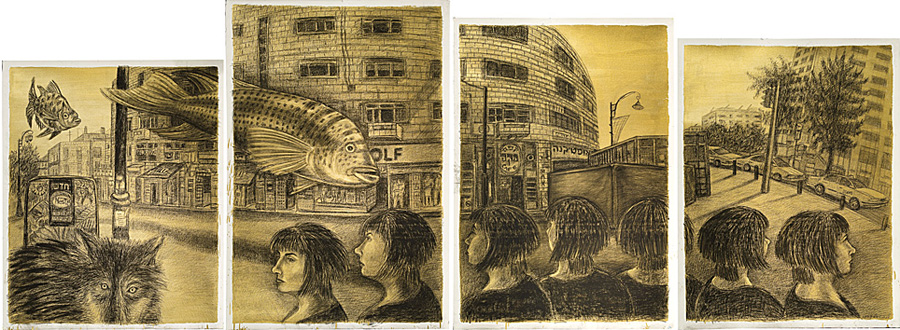

The quadrilogy “Y-M,” the third part of the grand trilogy, hesitates to proclaim Jerusalem´s full name, in which the whole, shalem, is inscribed. Y-M is the Hebrew acronym for the city´s name, in daily use only in advertisements or addresses. However, it implies the double symbolic opposite of Jerusalem – yam (the sea) and yamma (westward). It is an acronym-noun bereft of double meanings, a sunrise-less east. The wolf directing its gaze at the viewer signifies the vacuity, demonstrating the still sound of melancholy. The figure panoramically overlooking the empty and silent residential space is a mystical or shamanic statement of Zaidel´s that is inherent to the great Symbolist tradition. Seven gazes in all, juxtaposed against the seven spiritual bodies, the astral planes, the heavens, etc., all of which are dimensions of out-of-body experiences, of which this painting could be one, all expressing the passion to venture beyond the given and seemingly trivial. However, the cultic and neutral placement of the figure, and the absence of clear signs of ecstasy, spiritual transfiguration or even a melancholic expression, for some reason keep at bay those aspects, which are occasionally implanted in Zaidel´s work. Either way, the ritual-like circular turning of the gaze strives to represent finite and infinite, single and multiple, full and empty, the continuous whole, juxtaposed against the broken and fragmentary that is both exposed by and affiliated with the broken heart and gaze of the Broken-Hearted City Center series, which therefore turns this painting into a ritualistic-magical act of mending and unification.

Jerusalem – The Draining Site for the World´s Depleting Holiness

“There are ten degrees of holiness. The Land of Israel is holier than any other land … The walled cities [of the Land of Israel] are still more holy … The Holy of Holies is still more holy…” The Mishnah, in the first chapter of Tractate Kellim in the Order of Purities puts forth the strongest assertion of late Jewish religion in relation to the hierarchy of holiness, which in itself is dependant upon additional hierarchies – of man, place, time, cult, etc. In fact, no other religion went farther than Judaism in domesticating and demarcating holiness, and this demarcation and domestication are gradually retracted from the lands of the gentiles, distilled as they pass through narrowing rings until they reach the draining pipe protruding between the cherubim in the Holiest of Holies on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, and into the heavens. The Judaic hierarchy of holiness presides over the person´s entire life and possessions without any exception – place, time, the male body, the female body, the animal body, sexual relations, homes, possessions, language, even emotions and thoughts. This Jewish perception of holiness was so influential within the religious-spiritual sphere that we can no longer imagine holiness without its well-known opposites, the respective degrees of defilement and their entailed fences: expelling, separation, demarcation, hedging, isolation, abstention, consumption, elimination, monitoring and control, and many other such measures.

As said, the hedges, barricades, walls and numerous means of demarcation with which Zaidel´s paintings are strewn should be understood in the following sense – as hinting at this isolated and isolating paradigmatic hierarchy of holiness; as an organizing and constitutive principle that presides over life, whose center of magnetic power is located in the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, from which it has been spreading throughout the world for two thousand years, “For the Torah shall come forth from Zion.” It is easy to see how this religious principle was replicated by the core of the Modernist project as a fundamental structure whose center of gravity shifts from place to place. Since, in a certain sense, the industrial factory, its rational and estranging demarcation from humanity´s spiritual world, corresponds with and emphasizes further the instrumentality of the Holy of Holies; as if this holy site, in this order, was not the site for the convergence of holiness, but rather the site for its draining and escap. Instead of the animal sacrifices of the ancient past, it is holiness proper, or perhaps God Himself, who have been slaughtered in the past few centuries. In this sense, God´s divine presence on earth, known in Jewish tradition as the Shekhinah, is not awaiting redemption in exile; it is increasingly lost to the world.

That is why Zaidel´s wolves on the Temple Mount, in what could be a preposterous symbolic wish, are not defiling but are rather harbingers of holiness; their heartwarming movement between sites and things, with Zaidel´s odd self-conscious wink, endeavors to recall the continuum of holiness now lost, the primordial intimacy of being in the world like water in water. The wolves are the “shakers,” violators of the old order who at the same time are conductor of ancient holiness, the continuous holiness that the wild and undomesticated beast is its unequivocal symbol. That is why it is natural that no challenge, bordering on the declaration of war, was proclaimed by universal spirituality against particular religious spirituality in the modern age. In Modernist art, perhaps more than in philosophy and science, this struggle had far-reaching implications. But the exclusive and direct field in which this struggle is heard loud and clear is Symbolism, where the conflict appears as more ambivalent and perplexed than in modern art. Lena Zaidel´s voice is directly descended from this struggle, despite running the risk of anachronism.

Post-Post Symbolism

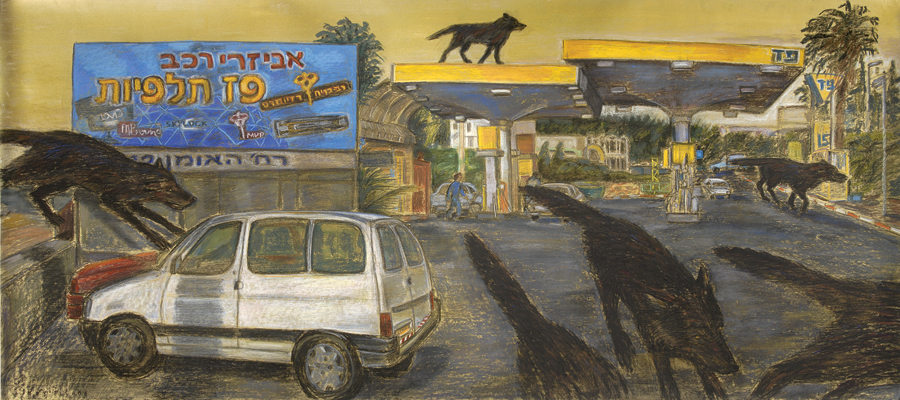

Zaidel´s Symbolism does not follow the movement´s romantic, traditional, mental and emotional school that drew directly on Romanticism. It is not an allegorical Symbolism that moves its signifiers with an open, somewhat dry eye, across reality, fermenting and bringing to the surface its hidden and covert phenomenological content. This painting was birthed either by the implicit and complicit random inventory of reality, or by an intuitive pictorial vision. Instead of a dream, it promulgates a self-aware vision, hallucination becomes visual enlightenment; allegory becomes a dialectical argument. This is a form of self-conscious Symbolism, which is narrating, conclusive, openly gathering from the inexorable abundance readily offered by reality, which perpetually oscillates between continuity-chaos and an illusory dichotomous order. This painting is forthright and congested, as its possible interpretations, like in any Symbolist painting, can literally make one´s head spin. The repeated use of industrial gold paint and charcoal in many of the paintings posits these opposites as a conceptual premise in all of the works. But Zaidels´ characteristic explicitness sometimes lets the Symbolist ax down, as in the paintings “Paz Talpiyot,” thus creating a dizzying chain of signifiers that stretches between the policed holiness of the golden Dome of the Rock and the blackness of the filling station that peeks from the surface like capital, threading them together into a single hermetic, blank and impeccable system. Sometimes this explicitness becomes actual staging, in “Chair,” for example, where we see an “emptied” chair, perhaps implying at the throne of King David´s line, or at the Arc of the Covenant held captive in the middle of a Philistine-Palestinian back yard, which is emptied as well. And yet, the true play is staged by placing the chair in the midst of drumhead court martial proceedings, set up by humanizing the ridiculing, despising and emptying gaze of the wolf-beast, which is amplified threefold by the gazes of the wolves standing on the other side of the fence – together they turn the painting into a play within a play. This is a classic post-Symbolist work, which echoes both and at the same time decadence, Symbolism´s progenitor, and modernist Primitivism, its offspring. This painting does not address painting directly, since its object, the issue it seeks to address so consistently and adamantly, always remains outside of the painting, in reality and in language, which had lost its holiness after losing the inner meaning of visible things. And yet, Zaidel´s “Street Wolves,” are not oriented at an entirely different dimension of reality, but rather at that lost internality, which nevertheless peeks through and signals tirelessly within that very same reality; and in those very things that appear in the work as optimistic irony, it yearns: for the waters of Eden, for spring, for the signs of love, for convergence, for the crown jewel, for the basic instinct, for holiness.

Lena Zaidel: "Street Wolves" from Lena Zaidel on Vimeo.

Drawing Cities ,”Erev Rav”, Art Magazine / Albert Suisa

Lena Zaidel´s drawing Fence II from the series Broken Hearted City Center is clearly situated on the urban-nature continuum. The so brazen and vital image of the wolf bursts forth from the folds/fragments of a city whose contrast to nature is not as stark as the unrestrained, orgiastic antithesis to Nature of other cities around the world that have literally become monsters that devour it. Yet, something in Zaidel´s imagery causes me to be more accurate and to state that it is a female rather than male wolf. This is not so much on account of the symbolic connection between women and female wolves, but on account of the substantial (and perhaps exclusive) relationship of cities to masculinity and patriarchy. But let us not become confused: though grammatically, the Hebrew word for city is feminine, this is only because cities were created by men. Men alone have founded cities, constructed them or conquered them; murdered the men and taken the local women for themselves; designed them and established in them the absolute war of the city against female, matriarchal and uncivilized Nature. Furthermore, most of history´s greatest urban planners and architects have always been men. The stunning effect of introducing the wild, feminine animal as an image of self or “other” into the heart of the urban-patriarchic oppression is very familiar from Kafka´s stories. Zaidel´s use of this impressive image in the local context of Jerusalem is refreshing, amusing and inspiring.

Show More