From the book of Gideon Ofrat :”Beyond the Horizon“, The Levin Collection, Selected Works, Part III, Ofer Levin Foundation for Israeli Art

Lena Zaidel, All the Places are Holy, 2010 / Gideon Ofrat

In 2013, Lena Zaidel (b. 1962) – who immigrated to Israel from Leningrad in 1976 and graduated the MGA program at Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design – staged her exhibition “Street Wolves” at the Jerusalem Artists´ House. Large-scale paper sheets were hung conspicuously on the chamber´s concrete walls on which more and more packs of wolves raiding Jerusalem were drawn (in dry pastel and charcoal). The paintings belonged to the series All the Places are Holy created in 2006, in which the artist depicted her wolves, with strikingly realistic skill, close to the city´s limits or in the city center (the Mashbir building, a gas station, the water fountain in Gan Hapa´amon, etc.), and most of all – in the dumps she positioned adjacent to the Dome of the Rock, in the Nablus Gate car-park, in the Western Wall concourse, etc. “The wolf undergoes symbolist distillment and becomes a signifier of the absence of holiness,” Albert Suisa wrote in the catalogue of that exhibition. In an essay in the same catalogue, I noted the apocalyptic aspect of the paintings, although Zaidel herself insisted: “My wolves are good!” In a Jerusalem of neglect and waste, the common milieu in these paintings, however, the wolves inevitably call to mind bad wolves from fairy tales, Freudian nightmares (“The Wolf Man,” 1918), and even the wolf totem from Slavic rituals (as the artist´s family has Slavic roots). At the same time, considering Zaidel´s denial and the fact that, simultaneous to art, she is a meditation instructor, we may also construe her wolves as the opposite, complementary pole to meditative mythic motifs (panoramas with white swans) which emerged in her paintings in the late 1990s, and in accordance with her statement: “I need the wolves as a source of arousal, as an image that assures me of alertness, vigilance, healthy stress, something that prevents my energy from falling.” Elsewhere, however, Zaidel said things in a different vein: “The wolves arouse Jerusalem from its sleep, awakening the streets and the holy places. Wherev the wolves have tread will never be the same again. The wolves represent the threat on the old worldviews. […] They threaten the city…”

[1] Albert Suisa, “Holiness – Hidden Face,” trans. Orr Scharf, cat. Lena Zaidel: Street Wolves (Jerusalem Artists´ House, 2013), p. 55

[2] Gideon Ofrat, “The Wolves´ Riddle,” trans. Joshua Yair, cat. Street Wolves, p. 44

[3] Zaidel quoted ibid. p. 46

The Wolves´ Riddle / Gideon Ofrat

“Walk around the streets of Jerusalem, look for, inquire, seek in its market places if you can find anyone doing justice, seeking faith; then I will forgive them. … Therefore, a forest lion has attacked them, a desert wolf has marauded them, a leopard lays in ambush above their cities; whoever leaves them is torn apart, for their sins are many, their backslidings are great.”

(Jeremiah 5:1,6)

The first association, that which is called for and unavoidable, to the scene of wolf packs walking around the Jerusalem streets in Lena Zaidel´s pictures is the apocalypse: the vision of the end of Jerusalem, the holy city, the bitter and ultimate answer to the vision of the Heavenly Jerusalem of John — the holy Jerusalem descending from heaven, “prepared as a bride adorned for her husband” (John 21:2). Additionally, there is the direct Christian context to wolves in Jesus´ vision on the eve of his crucifixion: “I know that after I leave, fierce wolves will come among you who will not spare the flock” (Acts of the Apostles 20:29).

“All the Places are Holy” was what the artist called her 2011 series of drawings of Jerusalem wolves. However, the sanctity of Jerusalem responded with the banality of waste, garbage, rusty fences, forlornness, the paucity of the city´s materials is lacking in transcendence, and most importantly, almost empty of the presence of people. The vitality of people has been exchanged for the vitality of wolves.

Wild animals in the Jerusalem streets has a precedence in literature, and others have already noted the connection of Lena Zaidel´s wolves to popular fables, the poetry of Yehudah Amichai, to the book of Clarissa Pinkola Estés (Women Who Run with Wolves), and others. Even Balak, Agnon´s mad and rabid dog (in Only Yesterday), which terrified the city´s residents, can also be added to this frontier city of wolves. Indeed, whether intentionally or unintentionally, Lena Zaidel has entered a thick cultural forest filled with menacing wolves.

But no: “My wolves are good!” argues the artist, totally negating any apocalyptic reading of her paintings.

Good wolves?! Shall I agree to overlook the evil wolf of “Red Riding Hood” and “Peter and the Wolf”? Can I overlook the holocaustic interpretation in the context of my personal/psychological apocalyptic tendencies, not to mention in the context of the wealth of mythological sources regarding the wolf? Can one imagine that an artist would devote eleven years to painting wolves unless a psychological-anxiety “demon” was feeding this obsession? Furthermore: was it not Lena Zaidel herself who wrote, “The wolves arouse Jerusalem from its sleep, awakening the streets and the holy places. Wherever the wolves have tread will never be the same again. The wolves represent the threat on the old worldviews. […] They threaten the city.” And elsewhere: “Is the reality presented here aspiring to connect all its pieces, or perhaps this is a moment before the destruction?”

If so, then perhaps, the wolves do indeed symbolize threat and destruction? No wonder that I feel I must cite Sigmund Freud´s book of 1918, “The Wolfman,” and the nightmare of wolves that pursued Sergei Pankejeff, from the picture of a wolf he saw as a child and through the famous dream of six or seven white wolves sitting on a tree outside his bedroom window (Pankejeff: “In great terror, evidently of being eaten up by the wolves, I screamed and woke up.”). Freud, as known, interpreted the dream as a castration anxiety and saw the wolves as a father substitute, that is, an anxiety that his “predatory” father would eat him up. Are these also among Lena Zaidel´s wolves? Is the artist concealing a dark and terrible secret from her childhood? I feel I am getting carried away.

Still, under the heavy influence of being swept along by my interpretation of disaster, I identify most of Lena Zaidel´s wolves with the common Israeli wolf, and maybe even with the Canis Lupus Arabs, which is the Arabian wolf. Several hundred of this type, so I read, live in the Golan, the Galil and the Aravah. Aha! Arab wolves overrunning Jerusalem! In fact, why should I suffice myself with the Arabian wolf: The Jungian in me connects me to the wolf totem of the Slavic fables and rituals (Lena Zaidel: “I have some Slavic roots in the family.”), specifically to the god of the underworld, Dazhbog, who is depicted as a white, lame wolf. Slavic mythology tells of his descent to the underworld and his marriage with Morana, the goddess of death. The Jungian interpreter in me rejoices: here is the archetype, here is the wolf as a collective unconscious shaking the psyche of the artist who came to Israel from Leningrad in 1976 at age 13….

At this Jungian stage, I cannot avoid recalling Lena Zaidel´s series of large graffiti drawings of “Demeter,” which she displayed at “Kol HaIsha” in Jerusalem, at the end of 1999: the fragments of a nude woman in the image of Demeter, the goddess of crops, holding fruit and vegetables in her hands repeat themselves in these drawings, echoing in black and white, even if only from the distance, the story of Persephone, Demeter´s daughter, who descends every year to visit Hades in the underworld. The mother, furious at Hades, halts growth in the fields for the duration of the visit: autumn and winter….

Have we identified the key to Lena Zaidel´s wolves? Dark and threatening forces? Perhaps the anxiety of a mother (regarding the young woman painted among the wolves who have overtaken the fountain of lions in Jerusalem, the artist says: “That is our daughter”)? But no: Lena Zaidel´s insistence that, “My wolves are good!” leaves us no peace, especially since it is accompanied by absolute denials of any anxieties. This insistence challenges our interpretation of catastrophe; it forces upon us an effort to go beyond ourselves, to beyond the most available interpretation. On the practical level, it forces us to investigate the birth of the wolf in Lena Zaidel´s creations. And thus, the question that grips us now is: from where, from what, and when was the wolf in Zaidel´s painting born?

The answer to the “when” is simple: the first painting of wolves appeared in Zaidel´s creations in 2002 at a one woman show at the Jerusalem Artists´ House. There were about thirty paintings of wolves, painted in relative abstraction with mono-chrome oil paint, in the center of each being a pack of wolves, two to four, running after each other on an abstract and neutral background. These paintings of wolves adorned the walls of the Artists´ House in two rows, confirming a gradual color progression paralleling the colors of the rainbow.

But what preceded these wolves? Where did they come from? We mentioned the “Demeter” series. Preceding that, around 1998, was the series of Swans: the first ones were spontaneous pencil drawings of swans in the zoo; later came large and panoramic emulsion paintings, in which white swans were painted on a gray-silver background in a semi-pointillist style. The series was never displayed, but its content as a wall installation embodying a “meditative character” is stressed by the artist.

Meditative is a key word into the world of Lena Zaidel, who also teaches meditation and has even studied the Theosophical teachings of Blavatsky, Steiner, and others. The swan, she points out, symbolizes a spiritual path by its existence in water, air and land, which symbolize three states of consciousness. To this aspect of meditation in Zaidel´s paintings is added the large panoramic drawings, etched with charcoal in 2005, representing a sort of scenery of grayish hills. The earlier ones depict winding paths and light-shade contrasts, but the later ones are devoted to great and soft peace, and are wrapped in transcendental spirituality.

More and more I begin to grasp Lena Zaidel´s affinity to “the spiritual in art,” as Kandinsky put it. “From the age of four I wanted to be an oracle,” she says, “and for two years I actually worked as one. I used to read cards.” To this piece of information I add Zaidel´s enchantment with temples (“My dream is to go on a world-wide journey to temples!”), as well as her series of drawings of the Monastery of the Cross of 2005: shades of protage, in which the monastery appears as a flat, abstract, mysterious and quiet image, but also somewhat threatening. I imagine monasteries as places of inner peace and a search for the sacred. “I was hypnotized by the place,” Zaidel points out, when she talks about her repeated stays at the Monastery of the Cross.

If so, we have meditative painting on the other hand, and paintings of wolves on the other. The fact is: in that same year, 2005, around the time of the monastery paintings, Zaidel painted two giant and realistic pastel paintings of a wolf staring at … a lemon. A wolf and a lemon??!! “These two have no connection; they are unable to make contact with each other,” the artist explains, as if the paradox itself is sufficient for her. But I, who am captivated by metaphors and allegories, wonder about these pairs of paintings: who is threatening whom? Who is big and who is small? And is not the paint of the lemon identical to the paint of the wolf´s eyes? And why a lemon and not, for instance, a strawberry or an apple? Thus, I returned to the vicinities of evil, or at least — of the sour. However, more than anything else, I ask myself: if a wolf and a lemon are unable to challenge each other with a productive dialogue, what contrasts do they possess that can fecundate the artist´s psyche?

Meditation on the one hand and wolves on the other. “I need wolves as a source of arousal, as an image that assures me of alertness, vigilance, healthy stress, something that prevents my energy from falling,” Lena Zaidel says in explaining her need for wolves. As if the wolf is nothing more than incidental (after all, couldn´t panthers or lions have served the same purpose of being an “arousing image”?). The wolf seems to be so incidental in the artist´s consciousness, that she even connects it with a friend named “Zeev” (wolf), who ordered a painting of a wolf, which was how the whole thing began. “And if his name had been Tzvi (deer), would you have painted packs of deers?” I challenge her. “Yes,” she answers.

But I think differently: in my opinion, Lena Zaidel´s creative psyche sways between two poles: at the one, the abstract, she aspires for sublime spiritual peace, of the meditative and sacred type. However, at the other pole, the realistic, she is drawn to the earthy, the bodily, the animalistic, the energetic, which the wolf depicts in her creative works. This itself is the “threat” which arises from her above quoted words about wolves as arousing from the slumber of routine and the inertia of stagnation. Lena Zaidel´s paintings are stretched in both directions, which fecundate each other: the meditative grows out of the “wolfy,” and the “wolfy” from the meditative. The duality of peace and vigilance, of the good and the threat, the sacred and the profane, the spiritual and the earthy, the salvation and the apocalyptic. Jerusalem, the heavenly bride, in contrast with the wolf of the underworld. This duality is a creative split.

In his book, “The Hidden Order of Art” (1967), the Freudian psychoanalyst, Anton Ehrenzweig, analyzes the artistic creative process as an anal psychic movement between passivity (creative constipation) and activity (a creative outburst of releasing “buried” psychic charges). It seems that Lena Zaidel´s creative movement between meditative and “wolfy” confirms a parallel creative process, in which each pole alternately gives birth to the other.

This is indeed the ancient and well-known split between the Vita Contemplativa and the Vita Activa, a value split which the Italian humanism of the Renaissance used frequently as an idea (Petrarch) and in painting (Bondone, Leonardo, Raphael). This is the distinction between a monastic life (Vita Contemplativa) and life outside of a monastery (Vita Activa), between the sacred and the profane, between the passive and the active. This duality is Lena Zaidel´s.

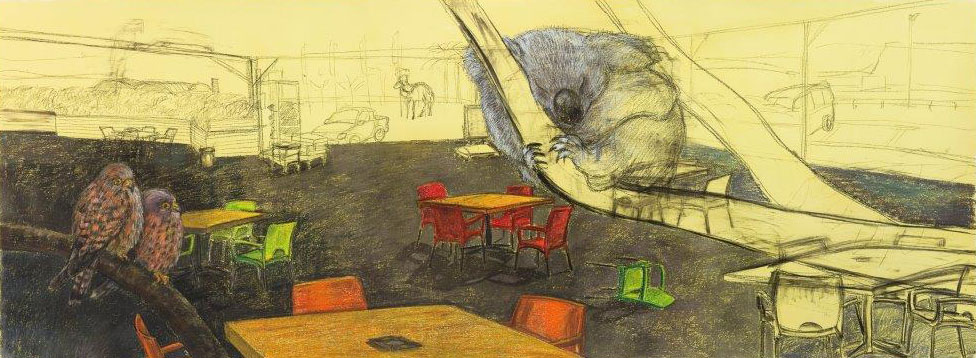

At this very time, she has completed a wide pastel painting on paper, in which the realism borders on a sketch: a cute koala bear is falling asleep on a tree trunk hanging over the vacated space of a coffee shop on the way to Jericho…. The Freudian dream of wolves has evolved into a dream of Australian koalas on a tree. A moment of peace in Lena Zaidel´s world? A moment before the returning of the wolf?

Gideon Ofrat, Curator, philosopher, art critic

Translation: Yehoshua Yair

For Lena Zaidel´s catalogue of the exhibition: Street Wolves, 2013, Jerusalem Artists´ House

Show More